If I had to give him a grade on walking, he would have earned an F that day based on standardized benchmark data for the

What causes this shift in learning when our brains naturally crave growth? More importantly, is there a way to reverse this trend? I see two impediments that have inhibited learning in our students. One is fear of failure. The other is risk aversion. When we overcome these two obstacles, love of learning will flow unimpeded.

As our school moved to a S.T.E.M. based curriculum[1], I have seen these two hurdles shrink. They disappeared altogether or at least became surmountable. Students were again excited to tackle problems and to conquer material and skills they had not yet learned.

I believe this is because a S.T.E.M. curriculum can be taught using a circular model instead of a linear one. Here is what I mean by that. Under a typical instructional model, students are led through new material that progressively and sequentially develop a skill or skills. At the culmination of the unit of instruction, they are assessed. Students who lack the skills may end up with a failing grade. That is like walking down a long one-way road only to find a “dead end” sign.

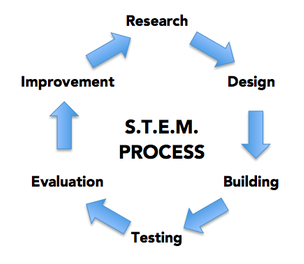

When I teach S.T.E.M. I present a circular model of instruction to the students as shown here. Students are given a problem to consider. They conduct research to give them a head start on the problem-solving process. Then they design a solution, build it, and test it. Rarely do they succeed on their first attempt.

If their evaluation shows that they haven’t solved the problem, they improve their solution by going back through the cycle until they are satisfied with their solution.

Failure is no longer a dead end; it is an opportunity to restart with more and better information.

I still hear, “This is a lot harder than I thought!” but now they say it with a smile and add, “Can I try again?” In fact, even when students find a solution, they often want to repeat the process to do even better.

Recently I challenged my students to build a vehicle powered by vinegar and baking soda out of a plastic water bottle and some wheels. The early attempts were dismal failures, much like my son’s first steps. But with each iteration of the S.T.E.M. learning cycle, they got closer to a solution. One team had finished and earned an A on the project, but when they saw another team beat their distance record, they re-entered the cycle and created an even better vehicle to retake the lead.

My students were energized, excited, and eager. They lost their fear of failure. Even when one of the chemical engines exploded in a student’s hand covering him in vinegar, he simply built a new model. Risk aversion didn’t dampen his spirits as much as the vinegar dampened his clothes!

This has caused me to reconsider how I teach other subjects. What constitutes failure and success? In my digital photography class, some students did not have their portfolios ready when I graded them. Of course the computer showed an F on the assignment, but my approach to the situation was, “How can we fix that? What do we need in order to get those assignments turned in?” Will they get full credit when the assignment is late? That is a separate and individual question that will vary from teacher to teacher or even from case to case. Is it late due to a technology issue? Is it late because the student was not using time wisely? However the emphasis shifts from, “I have an F,” to “I have an F. How can I improve that?”

This type of instruction common to engineering and S.T.E.M. environments is a natural way to learn. This is how problems are solved in the real world. When a problem such as the invention of the light bulb was addressed, Edison and his team repeated many thousands of cycles of research, design, building, testing, evaluation, and improvement. When asked, “Didn’t you get discouraged when you failed so many times?”

“I have not failed. I’ve just found 10,000 ways that don’t work.”

If you are interested in S.T.E.M. based lessons, you may wish to look over some of my activities on the subject found under the resources tab of my website.

Watch a video by clicking here.

Read another article about Brad's class here.

[1] Learn more about the integrated teaching of science, technology, engineering, and math in my other blogs by clicking here.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed