It was the first week of school and I held up a chessboard in my honors class. “How many squares are on this board?” I asked. One student raised his hand and said there were 64. I asked him how he got the answer.

“I multiplied eight times eight.” I asked him to stand up along one wall of the classroom and instructed anyone who agreed to stand with him. About ten students remained in their seats. I asked one of them what he thought.

“I saw this problem on Facebook,” he said. “There are lots of square shapes hidden on the board.” A look of horror spread across the students’ faces as they realized the magnitude of answering my question: how many squares are on a chessboard.

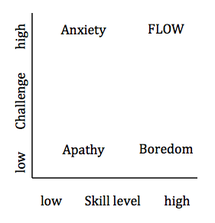

Stallard describes personal growth as the perfect match between skills and challenge. When we encounter a challenging task and operate at a high skill level we enter what psychologists call a “flow” state.

Though the definition of flow is sometimes nebulous and abstract, it is easy to recognize by its characteristics. In a flow state, one loses sense of time. Performance is maximized as the worker is immersed wholeheartedly in the task and works at his or her best. Flow states are often described by artists, musicians, athletes, and, yes, children playing video games. A flow environment is more difficult to establish in the workplace and even more uncommon in the classroom.

However, enough research has been done in this area so that we know the conditions that can maximize such an environment. Schaffer (2013) found seven factors that are necessary for maximizing performance in a flow state:

- Knowing what to do

- Knowing how to do it

- Knowing how well you are doing

- Knowing where to go next

- High perceived challenges

- High perceived skills

- Freedom from distractions

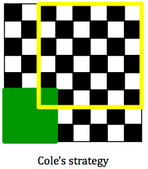

By now the period was over. At our next meeting, we reviewed the problem and students shared how they were progressing. When one student mentioned about moving the folded piece of paper, Cole mentioned that in his group they didn’t actually move the paper. Once Cole placed a three-by-three paper in the lower left corner of the chessboard, he realized that the upper right corner of the paper could occupy any of the 36 positions in the yellow six-by-six square shown. During this second class, students were showing me that they met conditions one through four of Schaffer’s list. In fact, as they continued to work, the room became noisier and noisier. The students were excited and were discussing the task with wild enthusiasm. When I had to interrupt them to give them further instructions they resented it. They wanted freedom from my distractions – condition seven. And when I told them it was time to clean up, they were shocked.

In fact, I suspect that some of our failures in tracking students might be attributed to a poor match in these two factors. For example when students are misplaced in remedial classes due to low grades, poor homework habits, or behavioral issues, we might find students with above average skills in a class where the challenge bores them. If students’ skill level and task levels are both low, we encounter the apathy common in remedial classes.

Likewise low skilled students could feel undue anxiety when placed in courses where the task far exceeds their skill level. However I have had success in the past when I personally invited such students to try my honors class. Typically they welcomed the invitation and rose to the challenge. Their self-esteem rose also.

Prior to our next meeting, we took all of our students to Lassen National Park and had them climb a volcano as part of our character education program. (For more information on this, see The Seven Noble Tasks on the store tab of my website.) They had seen pictures of the mountain but were stunned to see how large it loomed in real life as they struggled to reach the summit. At our next class meeting, they finished their performance task on the chessboard question. I asked them to show how they had solved the problem. They also had to explain in a paragraph how tackling this question was like climbing the volcano.

Many students said that at first the task looked small, just like the volcano in the picture, but when you actually saw the magnitude of it you thought, “There is no way I will ever get to the top of this.” The struggle was difficult, but after a while you could see how much progress you were making, and it empowered you to go on. The people in the math group were like friends who hiked alongside offering encouragment. Once you reached the top, you felt like you could accomplish anything. I was amazed at the enthusiasm the students showed at the conclusion of the assignment and also at how eagerly the tackled their next performance task.

Csikszentmihályi (2005) says that to enter into a flow experience you must have a clear goal. The task must also provide immediate feedback on your performance so you can make adjustments during the process. Lastly, the balance between task level and skill level must be good so that confidence is maintained.

Because of this, I now make a greater attempt to find that perfect match between skill level and task. I also look for problems in which students can see clearly that they are making progress. I also ensure that I clearly explain the goal of the task and bring their attention back to that goal frequently.

Mathematics is a subject area in which many students lack confidence and feel great anxiety. As teachers, we can design tasks that are a good fit for our students’ skill level. We can also help to establish a classroom environment in which these conditions that promote personal growth are more likely to be met. Moving in these directions will help our students achieve greater growth and hence much greater classroom success.

Csikszentmihályi, M.; Abuhamdeh, S. & Nakamura, J. (2005) “Flow”, in Elliot, A., Handbook of Competence and Motivation, New York: The Guilford Press, pp. 598–698

Schaffer, Owen (2013), Crafting Fun User Experiences: A Method to FAcilitate Flow, Human Factors International

RSS Feed

RSS Feed